Household Air Pollution in Jamaica

There are many things going on in your kitchen that you just do not see.

By Alistair McLean | October 10, 2020

Some of my favorite childhood memories involve food. When I was growing up in Jamaica, Sunday dinner was the culinary highlight of the week. At my parents’ house, meat – chicken for the most part, but sometimes oxtail, or fish – was seasoned on Saturday afternoon and allowed to marinade overnight. Chicken then baked in the oven low and slow for hours on Sunday afternoon until the meat was tender, juicy and so full of flavor that each bite made you feel everything was right with the world. Oxtail sat in a pressure cooker along with beans, herbs, and spices; the cooker would whistle and hiss merrily, reminding everybody that something good was coming up. While the meat was gradually approaching perfection, rice and peas cooked slowly on a burner next door. Red Snapper was the favorite fish, seasoned to perfection, it would be partially fried then steamed, yielding a gourmet’s delight with delicious, mouthwatering gravy. For special occasions, the fare would be complemented with a pot of potatoes on the stove to make potato salad and another pot to boil macaroni for baked macaroni and cheese. Meanwhile, at the counter, mom and dad made tossed salad with fresh veggies, and a delicious fruit drink using some combination of mangoes, passionfruit, guavas, oranges and soursop.

My folks were not the baking types, except for one magical night during the Christmas holidays when they baked five traditional Jamaican Christmas Cakes. My parents did it the right way in a monumental baking operation that resembled the technical challenge on the Great British Baking Show. Dried fruit that had spent months soaking in red wine was combined with flour, molasses, rum, butter, eggs, and other ingredients. By midnight, five cake pans of black gold appeared on the kitchen counter where the cakes slowly cooled off. The bakers sweated profusely by the end of the baking session from buzzing around the kitchen and occasionally opening the oven to check on the progress of the cakes.

As a small kid, I assumed that cooking and baking were only done using a gas stove, but I came to realize how wrong I was. At the age of eight or nine, I noticed a man fussing over a huge mound of soil with smoke rising from all sides, always in the same spot – an empty lot adjacent to a highway next to an irrigation canal. Periodically, the mound was taken apart and the contents removed, but soon after, a new mound emerged. One day I asked my dad about the mystery mound. He told me about the process of making charcoal, which requires setting a pile of wood ablaze, then piling soil on it to cut off the oxygen supply and finally retrieving the wood after some time before it burnt out completely. Charcoal, he explained, was a vital cooking fuel source for many Jamaicans. Dad used the opportunity to tell me about the way food was cooked when he was a boy. Grandma would situate a large pot on three stones that sat on an elevated platform. She inserted dried wood between the stones, doused a piece of paper with kerosene, put the paper in the wood pile and then lit it. The flames eventually died down, but not before producing a lot of smoke that escaped through a small window in the makeshift zinc shed next to the house that served as the kitchen. Grandma stayed close by to stir the pot periodically, add ingredients, insert more wood and remove ashes from burnt-out wood.

With so many wonderful memories linked to it, cooking is such a common, mundane activity that we rarely think of it as a health threat. And yet, we should. The reason is that indoor cooking gives rise to unsafe levels of air pollution in a home. For a long time, I associated air pollution with the stifling stream of exhaust from the tail pipe of an old diesel truck or the dust from the sand and cement used to construct new homes in the community where I grew up. However, according to the Rocky Mountain Institute, most stoves produce harmful particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5) and ultrafine particles (UFP) when used for cooking. Gas stoves specifically emit a range of pollutants, such as particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and formaldehyde.

Around the world, approximately 3 billion people cook using solid fuels such as charcoal, wood and animal dung, according to World Health Organization estimates. This practice leads to the death of about 4 million people annually from illnesses caused by indoor air pollution resulting from cooking with solid fuels. Indoor air pollution is linked to strokes, heart disease and lung cancer. Children are particularly vulnerable because their lungs are still developing, while their activity levels are significantly higher than those of adults: children breathe much faster, exposing themselves to more harmful substances. Besides detrimental lung health effects, recent research points to cognitive impairment in school-age children as a consequence of their exposure to air pollution.

My parents moved from the rural areas of Jamaica where they grew up as children, obtained college degrees which led to decent jobs and the wherewithal to provide a middle-class lifestyle for my brother and me. This meant using a propane-fueled gas stove for all our cooking needs, rather than solid fuel. Propane provided a cleaner-burning fuel alternative because it produces less particulate matter than solid fuels. This was an improvement, but did not completely eliminate substantial gaseous emissions from our kitchen.

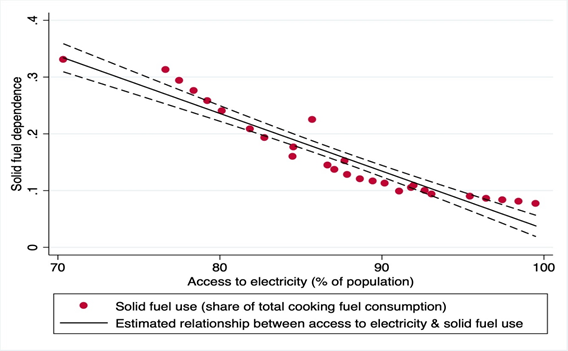

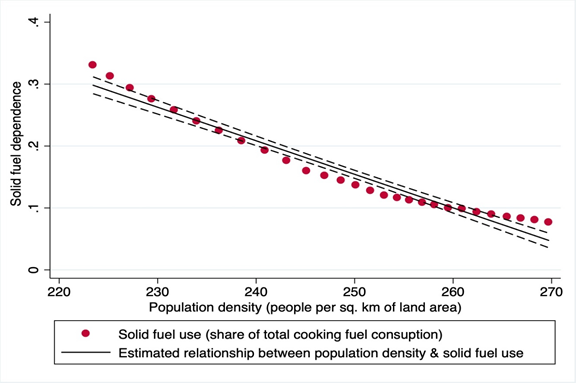

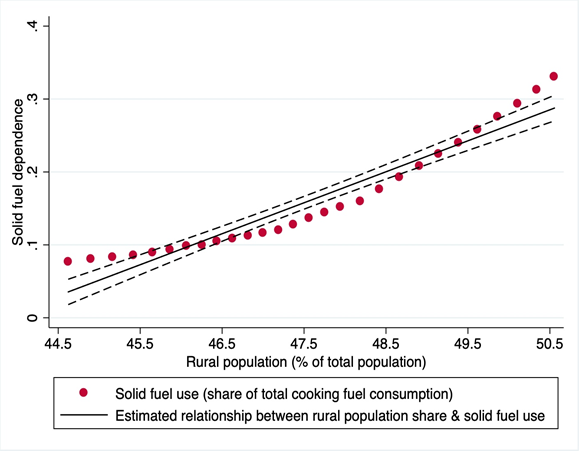

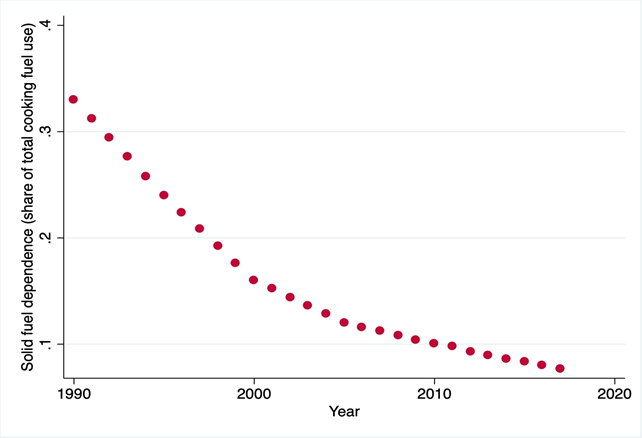

So, was that the solution? In order reduce reliance on solid fuel, do people need to relocate to cities and leave their solid fuel stoves behind? As it turns out, research on the use of and transition away from household solid fuel suggests that factors such as improved access to electricity, increased population density and greater urbanization have a negative relationship with solid fuel use. Jamaica’s overall solid fuel dependence has declined dramatically over time. At least in part, we can thank nearly universal electricity access (99 percent of the country’s population), growing population density (271 people per square km in 2018, up from 223 in 1990), and urbanization (just 44 percent of the population now reside in rural areas, compared to 51 percent in 1990), as World Bank data show.

Figure 1: Negative relationship between population access to electricity and solid fuel use in Jamaica

Figure 2: Negative relationship between population density and solid fuel use in Jamaica

Figure 3: Positive relationship between increasing rural population and solid fuel dependence in Jamaica

Figure 4: Declining trend in solid fuel dependence in Jamaica over the 2 past decades

Yet, the kitchen unquestionably remains the heart of the home, regardless of where the home is located. How can we make it safer? The good news is that, overall, Jamaican households rely on solid cooking fuels much less now than three decades ago: only 8 percent of households cooked using solid fuels in 2017, compared to 33 percent in 1990. The bad news is that approximately 80% of Jamaicans now use gas for cooking, despite the fact that emissions from gas stoves present an environmental health hazard. While heavy solid fuel dependence is no longer an issue, remaining indoor air pollution is still a troubling threat to health.

Here are some simple solutions to improve the air quality in the kitchen – and help your entire family breathe clean air at home:

- Open a window in the kitchen while cooking and give the neighbors a serious case of cooking envy. If you drive around densely populated communities like Portmore and Ensom City on a Sunday afternoon between 2:00 p.m. and 6:00 pm, you will treat your nostrils to the dazzling selection of smells that will make you question your dinner plans. Let passers-by take in and enjoy amazing scents of your slow baked chicken, curried goat, fried fish and bammy, peppered steak and rice and peas! Opening windows is an easy and low-cost solution to expelling the gases produced by cooking on a gas stove.

- Put a box fan in the window. A standing fan is already the go-to option for cooling down houses, but I bet you did not know that a window fan is an affordable option to improve air quality in the kitchen. A well-placed window fan can pull in fresh air from outside into the kitchen and help remove polluted air from the kitchen. And if you have an exhaust fan over your stove, don’t forget to use it!

- Use an air cleaner. The marketplace is filled with an assortment of portable air purification systems. However, do not be intimidated by the enormous range of available options. Make sure that the air cleaner has a clean air delivery rate (CADR) suited for the kitchen/dining room AND has activated carbon filters. The CADR scale goes from 400-450, depending on the particle size measured, where dust CADR can be as high has 400 and smoke CADAR can be as high as 450. An air cleaner with a high CADR and activated carbon filters will remove fine particles and gases and allow you to enjoy leisurely Sunday and Christmas dinners safely.

- Use an induction stove. Many Jamaican households prefer gas stoves because these are cheaper to operate compared to their electric counterparts, even though using an electric stove would significantly reduce household air pollution. It is easy to see why. When you receive your monthly electricity bill from JPS (the sole electric utility in Jamaica), it is enough to make you scream and avoid all electrical appliances altogether. There is also the taste factor: I have heard people say that cooking with gas makes the food taste better. I am not going to wade into this debate because I am more of an eating expert than a cooking expert. However, with more families trying to stretch their budgets, cooking efficiency should drive the decision of which stove to purchase. Let me introduce you to the induction stove. According to the Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings conducted by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, up to 90 percent of energy produced on an induction stove is used to cook the food, compared to approximately 74 percent for electric stoves and – wait for it! – only up to 40 percent for gas stoves. With induction cooktops, you do not have to worry about gas leaks, while their benefits include energy efficiency and the ease of cleaning.

By reducing indoor air pollution, households can significantly reduce respiratory illnesses and improve their quality of life indoors. Did you realize that indoor air pollution resulting from cooking was such a significant health hazard? What steps have you taken to reduce indoor air pollution in your home? Future editions of KTMC Perspectives will cover other sources of indoor air pollution.